Clive Davis was so impressed with a 1972 showcase performance of Aerosmith at Max’s Kansas City that he immediately signed the band to Columbia Records. But the very expensive, much-anticipated, self-titled 1973 debut album dropped with a quiet thud.

Promising young producer Jack Douglas was sent up to Boston to check out the band. He recalls, “They were raw and lean and hard. I just loved it. They didn’t really like anybody. They were tough kids, especially Joe Perry. They were like, ‘Yeah, fucking record companies. Fucking managers. Fucking producers. They all want to fuck us over. Who the fuck are you’.”

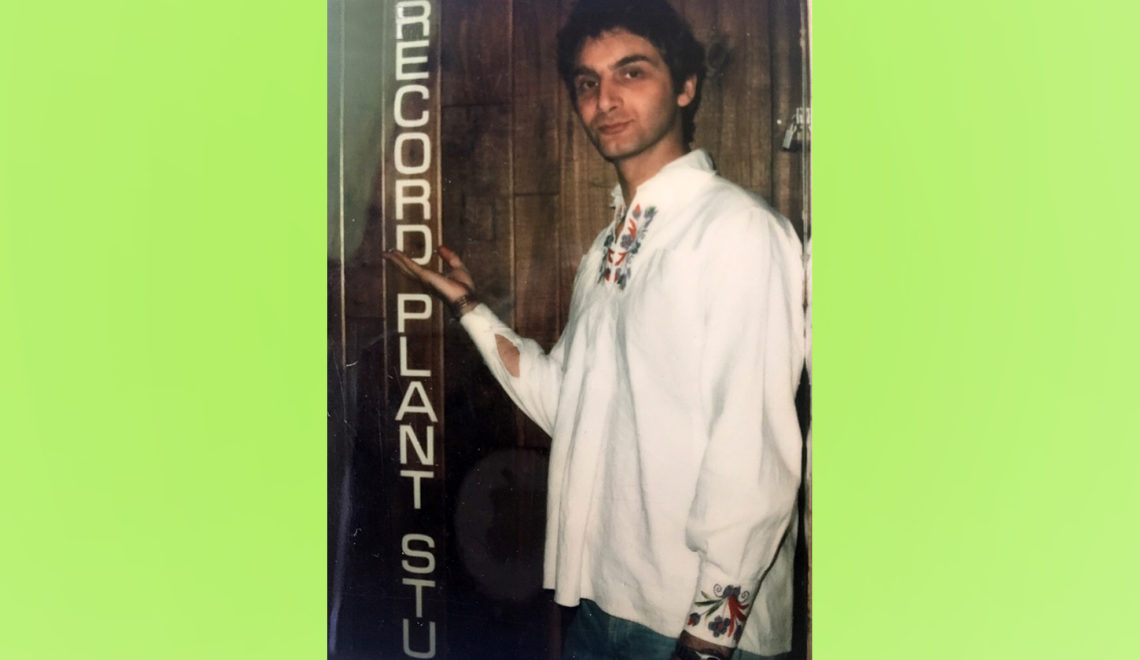

Douglas got his start in 1969 at Record Plant in New York City as a janitor, but within a few fast years was working with John Lennon, Cheap Trick, Alice Cooper, Miles Davis, the James Gang, and with Aerosmith. He is affectionately dubbed the sixth member for his contribution to arrangements and lyrics, as well as production. He produced the signature multi-platinum Aerosmith albums, two of which are ranked among Rolling Stone’s 500 greatest albums of all time.

The jump from recording engineer to producer happened when Douglas was engineering the debut New York Dolls album at Record Plant in 1973, ostensibly produced by Todd Rundgren, who has said that he barely touched the project.

Douglas explains this pivotal point in his career as an engineer, “Basically, it was your first really hardcore punk album. Todd Rundgren was the producer and Todd did not like the project at all and rarely showed up to the sessions. One very famous scene happened when the Dolls were out there in the room recording. David Johansen was in a booth doing a vocal just to drive the band. It might have been “Personality Crisis” or “Trash”, one of those songs, and when Todd arrived in the control room the band wasn’t sounding very good and he was complaining to me about how they can’t play, they can’t sing.”

Douglas takes it back a notch. “Todd was a great producer, and when David came into the control room after the take, Todd said to him, ‘Wow, you know, that’s going to be great when we add a lot of harmony to the vocals,’ and David looked at him and said, ‘Harmony? Are you accusing me of having melody?’ I saw Todd react, suspicions confirmed. These guys are anarchists. They’re not musicians, and I think David, who was a brilliant guy, just brilliant, was probably just kidding him in a way, you know? In some way he was playing with him, and so after that day Todd would phone in, ‘How’s it going?’ I would tell him it was going good and he’d say, ‘Well, I can’t make it.’

Douglas had been on the road as a guitarist from ’64 to ’69, backing up Chuck Berry and other headliners. “Having been a touring and recording musician, I had the emotional makeup to work with other musicians in a different way. I was living downtown, down Fifth Street between A and B. I was a downtown guy, I was a Max’s Kansas City guy. I had some rapport with the band and we got that album done. For better or worse, it’s considered a classic now. People thought it could never be completed. We had to run interference every time somebody from Mercury came by to check us out. I just did what I had to do to get the record done.”

Producer Bob Ezrin, who was working at Record Plant with Alice Cooper, liked the Dolls and used to drop in. Douglas remembers Ezrin’s observation, “You know, you’re producing this album?” I just shrugged and told him, “I’m doing the best I can just to hold the kit together, Bob.” Douglas later did some engineering on Cooper’s “School’s Out” and “Billion Dollar Babies” and Ezrin was further impressed with his ability to work with musicians and encouraged him, “You know, you really have the chops to be a producer.”

Douglas explains, “I have a composition background and a playing background and I think my natural inclination and personality is one that really respects the artist’s viewpoint.” Ezrin, a Canadian, suggested that Douglas go to Toronto and refine his producing abilities. “So this was my out of town opening, and I produced a band called Crowbar and the album went Platinum. Did I know what I was doing, no, but I was able to make as many mistakes as I possibly could. No one knew it. The album sold well. It was a big album in Canada. When I came back to New York, I was asked to produce Aerosmith’s second album, which ended up being ‘Get Your Wings’.

Joe Perry remembers Ezrin and Douglas riding to the rescue. “They really pulled my nuts out of the fire, because Columbia was going to dump us after the first record. Then when Bob came around he got Jack in the driver’s seat, it was like, okay, we’re set to go. But this record was the first one that didn’t include a bunch of material that we’d been playing for years in clubs and theaters and on the road. It was the first time we had to go in and actually write stuff on the clock, and so it was the first record where we moved past the sophomore blues. We got to use the Record Plant and Jack was there to help us, kind of guide us through that.”

“The big challenge for the band was that Joe and Brad were not the guitar players they had in their mind to be,” says Douglas. “They wanted to play these solos like Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton, but they didn’t have the technical expertise to do that. I suggested that for a number of tracks we bring in someone else to play the leads. They wanted to kill me. ‘What! On our own record. Some of the most important leads on our own record?’ I said, ‘But no one will ever know. We are not going to announce it. There would be no names on the record.’ I brought in Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner. One guy became Brad and one guy became Joe and they played very important solos across that album. Steven, by the way, was totally with me on this.”

Steven Tyler’s vocal style became something very different on the album that Douglas was producing. “I insisted that Steven sing with his real voice. On that first album he had this voice that wasn’t even him. It was like a made up voice that he thought sounded English or something.”

Perry remembers an early clash in the studio with Douglas. “Bob Ezrin was in the studio. I think it was one of the first times we were all in the studio together. Bob Ezrin was in there, Jack was there, maybe some of the record company guys were in there in the control room. We’re out in the studio, getting the headsets adjusted, and all of a sudden this ear-splitting feedback shoots through and just about bounced the headphones off my head, it was so loud, and I just let loose a stream of “Fuck, oh, fucking, fucking motherfucking, and what the fuck, you guys fucking can’t do anything right,’ and suddenly it’s dead quiet, dead silence.

“Jack walks up to me, kind of squats down next to me, pulls the headphones off my ears, and he goes, ‘If you want to talk to me, let’s go in the other room, but if you talk to me like that again in public, I’m going to have to bust you in the jaw.’ That’s when I got my first lesson in studio etiquette. Ever since then, we’ve been buddies.”

Douglas was not only amping up the guitars, he was vocal coaching the star. “I said, ‘You gotta be kidding me. With the pipes that you have, there’s no way you are going to sing, ‘Dream On, that way. Let’s get back to your real voice.’ He said, ‘I haven’t used that in a while.’ I said,’ Lets use it on this record now. We are going to establish your real voice.’ When that album came out I got a lot of hate mail from fans saying what did you do to Steven’s voice, but it paid off, as did the ghost guitar players who taught Brad and Joe how to play those solos that were on the record. Note for note, here is how you do it. The band went out on the road for a year and came back to me to do Toys in the Attic. When they came back they were totally different. They were great players.”

Aerosmith had opened for much bigger acts, like the Kinks, and they were starting to upstage the stars. They were also learning quickly about the dangers of egocentric excess. Perry explains, “We opened for the Dolls, you know? We saw them crash and burn. We didn’t want that to happen to us. They were the shit at that time, and we were opening for them, and they would pull stuff like calling the managers up in New York and telling them, ‘Unless we get a case of champagne, we’re not going on.’ The show would get delayed a half an hour, and it wasn’t long before everybody got tired of it.”

Douglas adds, “Everybody did get tired of it, and that was the end of their career, but when Aerosmith came back off the road, they not only were road warriors, they were killer musicians, and they rocked so hard. And this was the first time we had a pre-production period. It established the fact that we were going to have long pre-production periods, because it’s easier to spend money in a rehearsal studio than it is to spend money in a recording studio. It meant that we went in with just germs of ideas, but Joe always had tons of these great riffs.

“Brad had riffs, and Tom had riffs, and it was a matter of sitting in a room and seeing where they were going, and Steven would act like a ringmaster, barking and jumping around and going crazy, and Joe would be the guy laying down the whole thing, you know, ‘Here I could go here, I could go there.’ It was a really interesting time to do it, turning little germs into songs.”

The recording studio environment in which Toys in the Attic was created was at a studio that was relatively new and very different than previous studios. The state-of-the-art was 16-track on two-inch analog tape. Was this limiting for Douglas and Aerosmith?

“We didn’t think 16-tracks limited us,” Douglas says. “These guys could play live. It’s not like Joey went out and played the drums and then we laid them in, and then we laid something over that, and there was a click track and all that. They just went out and played, all of them together. Once you got a headphone mix for the band and they could hear each other, they just let it rip.”

Perry continues, “Every phase of it was somewhat of a performance, even down to the end when we were mixing the album. My clearest memories are when we would do mixes, and Steven and I were always in the studio, right from the very beginning, right til the end. We would be there right alongside Jack and engineer Jay Messina. This was before automation and when we were doing mixes, everybody had to be there, turn the pan buttons and change EQ. Bring in a tambourine, hand claps, maybe a background vocal, and a rhythm guitar, popping in and out on one track. Every time you ran a mix, it was a performance, and then at the end, when it would go by, everybody would kind of, well, I missed this, I missed that, and then we’d go back.”

“Every mix was like an adventure,” says Douglas. “Joey would be in charge of the volume on his tom-tom fills, and what we’d do is we’d tape razorblades to the point where you had to stop. If you went any further, you cut your fingers. Drummers always want to go a little bit louder with their tom-toms, so we would tape these razorblades down on the faders, and you could push the faders right up, ba-boom ba-ba-boom-boom, and then put them back where they were, you know, just by that, but if you went a little bit further, yeah, ‘You son of a bitch.’

“It was, everybody hands-on, and we were recording to 16-track. If there was a space somewhere, like on a backing vocals track, if there was eight bars that were empty, and we needed it to put a tambourine on, we would stick it on that track for eight bars.

“We would actually cut the multi-track, put a leader in, and then record, we would record so that when it passed the leader, that’s where the backing vocal was would start, so we would take up every bit of space, and then if we had to continue the tambourine, we might go to another track that had some space. The track restrictions also forced you to go live to your EQ, your compression, your echo, as much as you could, to the track, as you were recording it. You know, one of the great things was recording his guitars with everything on them, you know. We’d go all the way on. You knew what you were doing.”

Toys in the Attic was one of the first records to use a bit of early digital technology, the Eventide DDL. “It was probably eight-bit technology,” says Douglas, “and it was the first Eventide product ever, and they brought it to us to use, and we used it like crazy. A lot of Joe’s guitar solos where you hear it both left and right and slightly, maybe slightly delayed on the right, is that original DDL, and the reason it sounds so cool is because it’s only eight-bit.”

Douglas also used a live echo chamber on the ground floor that sometimes had leakage from Manhattan traffic that was incorporated into the “ambience” of the album. Record Plant had a good supply of exotic and very expensive microphones. “Steven sang so hard and so loud that, if you put up a big diaphragm Neumann U-47 he’d blow it up. The capsule just couldn’t take it. So I would put a cheap stage mic, a Shure 57 in front of him, and then didn’t really bother to turn it on. I just put it in front of him so he could work like he was singing into it. But I was really using a Sennheiser shotgun like they used on movie sets. I would have that about 10 feet away from him, it’s up in the air, pointed right at his mouth, which, by the way, is a nice big target. You could get the full fidelity of his voice. Most of his vocals on Toys in the Attic are recorded at a long distance with a Sennheiser shotgun.

“Another thing that’s really cool and was secret for awhile, is the sound of the bass on Sweet Emotion. People ask me all the time, ‘How’d you get that? How did you get that bass sound? Well, the electric bass is doubled by a bass marimba, which is a marimba with tone bars that are so long on the low end that you have to get up on a ladder to play. Jay Messina, our engineer, also played vibes, and so I said to him, ‘Why don’t you double the bass line with the marimba’, which is that old, wooden vibe. Boom-boom-boom da-boom-boom — it had this percussion and a tremendously low note. It actually went an octave below the electric bass, then you’d mix those two together, and that’s the bass sound on that song. I had fun for years telling bass players that if they cut little V’s in their speakers, lot’s of little V’s, you could get that sound.”

Douglas elaborates on the situation with Tyler: “This was a time when we discovered that Steven was a tormented lyricist — a brilliant lyricist, but absolutely tormented, and as time went on, he became more and more tormented to come up with lyrics. The band, and particularly Joe, could just rip out these great riffs. Steven was a brilliant lyricist, and funny, and self-deprecating and aware of what was going on in the world and what was going on in the streets, but he had set a bar for himself that was so high that it was really difficult for him.”

Perry observes, “It is really hard to have everything make sense, tell a story rhythmically, rhyme, fit in the fabric, and he’s got his own demons that he has to satisfy. He would basically take the tracks, and put headphones on and just walk around wherever he could, whether it was walking around the block in New York or at his house walking around the yard, or walking around the neighborhood, and he would just kind of sing along to it until he got something.”

“I told the band we needed one more up-tempo track,” says Douglas, “and Joe plays a burner, a thing so hot and hard and heavy that we’re just totally blown away. It was the last track and Steven was struggling.” Perry adds, “It was one song after another until we got to ‘Walk This Way.’ We had all the music but no words.”

Record Plant was on 44th Street and 8th Avenue in Manhattan. “Eighth Avenue was called the Minnesota Strip, from 44th Street to 50th Street,” says Douglas. “They called it the Minnesota Strip because when girls arrived at the Port Authority bus terminal from Minnesota, for some reason, the pimps would approach them, and before long, they would be hookers. I mean, if you went up to a lady of the night on 8th Avenue, and you said, ‘Wow, didn’t I meet you in Minneapolis?’ She would say, “Yeah, maybe we did.” New York is the place everybody liked to go, but for some reason, it was the girls from Minneapolis that fell victim to these guys.

“Anyway, so you had a scene at night in the mid ’70s; it was wall to wall hookers, pimps, drug addicts, drug dealers, hustlers of every kind, up 8th Avenue near the Times Square area. And you had pickpockets, thieves, and all kinds of nasty people on Broadway going after tourists. 42nd Street was flophouse movie theaters. You’d be coming out scratching and itching after you left those theaters. I knew a few male hookers who used to bring their lunch there in the balcony where they would make their living. They actually went with a lunch pail to make their living up in the balcony.”

Perry remembers, “We used to walk home from the studio at 4, 5, 6 o’clock in the morning. We’d walk up 8th Avenue right in the middle of the street, because we had our guitars, and we’d go in a clump, kind of like one after another, and we’d walk up to the Ramada Inn, and we wouldn’t walk on the sidewalk, because we didn’t want to get too close to the alleys. We just walked down the middle of the street.” Douglas adds, “Someone might jump out of the dark alleys. I used to carry a 9 millimeter in a side pocket and a .45 tucked in my belt.” Perry adds, “It was a funky part of town.”

“It was bad,” Douglas continues. “I mean it was dangerous. There could be a gunfight in the street and you’d have to jump and run for cover, so it was bad, but we loved it. It was reflected in the music, really. We would go for walks sometimes and listen to the sounds of the street, to get lyrics. You’d hear these just amazing phrases, whether it was a hooker, or a pimp, or a drug dealer, they had these phrases that you’d never heard before, and they ended up on Aerosmith records, because Steven had an ear for that. He would catch a strange phrase and it would be useful. The song that ended up as Walk This Way was an instrumental track that Joe came up with that was just incredible. We recorded it, and we couldn’t come up with a lyric or a rhyme or a rhythm for a vocal. There was just no way that it had anything we could use.

“We thought we were going to have to lose the track, or maybe make it an instrumental, but it was so good and funky. The rest of the album was pretty much finished lyrically and the vocals were done, so we decided to take the walk to see if there was anything going on. The only problem was that it was a Sunday afternoon, and there was really nothing happening. When we got down to Broadway, we went up to 50th Street and we came back down Broadway. We went down 42nd Street where all the second run theaters were. We had decided to take a break from the studio, since we were batting our heads against the wall, and we went in to see Young Frankenstein, which had come out earlier that year and was still playing in this neighborhood. There’s a scene in Young Frankenstein, we’re all sitting there laughing our asses off, there’s a scene where Marty Feldman says to the people who come to the castle, “Walk this way,” and they all walk like a hunchback into the castle. It killed us. We were all like dying laughing, and we couldn’t get it out of our heads.

“We went back to the studio and we started walking around like hunchbacks, and when we put the track up, do-do-do-do do-do-do-do-do, it seemed like hunchback walking music. We’d walk around like, do-do-do-do do-do-do-do-do, then we started to, “Walk this way,” do-do-do-do do-do-do-do. Steven goes, “I’ll be right back.” About 45 minutes later, there it was.”

Perry remembers, “Steven left and was down in the stairwell, and he jotted it all down. I was kind of frustrated at that point, because I had written the music, and I’m sitting there going, ‘It’s going to end up on the fucking B-side or whatever,’ and it was because we didn’t have the hook. The vocal thing, and it was like, you know, it wasn’t like a rock song. I really had a vision of it being like a kind of a callback to our funky roots.”

“Steven came back with the whole thing,” says Douglas. “He started with the chorus, ‘Walk this way,’ and then he came up with the most off the wall verse, which was early rap, maybe the first rap ever. Be-bop-dooty-dot-dan-bot-bot boddy-da-doot-ba-bada-da-dow. I mean, where did it come from? Clark Terry, Count Basie, you know? Steven had those roots, mind you, because he had a big musical catalog, so he had a lot of that stuff upstairs, but that he went for that was amazing. I remember somebody calling me up when the record came out and saying, ‘Congratulations.’ I was like, ‘For what?’ It was a big hit. I couldn’t believe it, it was a huge hit.”

“David Johansen from the Dolls called me,” says Perry. “He said, ‘That’s the filthiest song I ever heard on the radio.’ That was the other thing — Steven always wanted to put the double entendres in his stuff to see how close to the edge we could get, you know, without having to have stuff beeped out. Obviously, the whole song is so lascivious.” Douglas adds, ‘Yeah, with her kitty in the middle, you know, swing like she didn’t care.’ ‘It was banging on all cylinders,” Perry adds. “’t was a compliment to hear that from David, because the Dolls were no slouches when it came to that stuff’.”